Deleted Shades of Grey section, 2010 |

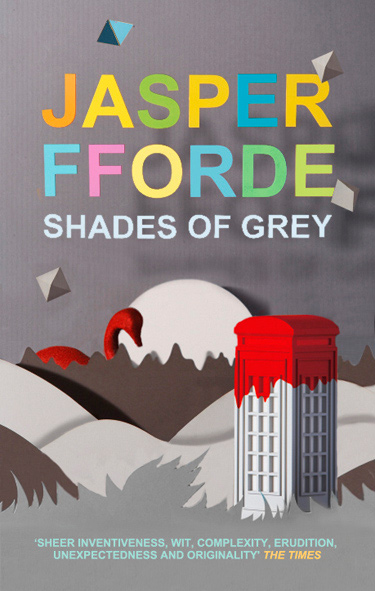

The original UK Hardback cover design for 'Shades of Grey'. After much thought and head scratching, it was decided that this cover didn't quite hit the right spot, so we went instead with an updated version of what went on the cover of the proof. |

| To those of you who have been to one of my talks, you may know that three books of ideas will often go into a single book, with a plethora of tangential thought being deleted because it doesn't work out, or I have a better idea, or there is some way it doesn't fit the story as a whole. And while seemingly a waste of time, it does allow me free rein to come up with often zany notions that appear only as throwaways, or, as in this case, potential for sequels. This 1200 word sequence was cut because it threw up another subplot where it wasn't needed, but since there are many references to 'Jollity Fair' (based on a Bonzo Dog Band Lyric) and that will be a a part of the sequel, ideas like this can be exploited at a later date - like the Fallen Man, Apocryphal Man, and, of course, the swans and barcodes. This section appears for the first time here, and features the 'Everspin', which, like the lightglobes that glow without being connected to anything, also hint to a power grid that is still up and running - working on the harmonics of music, as I recall - 'Megawatts delivered in the key of G'. Makes me want to write the sequel. Oooooh, Fforde, don't be a tease. DS-4 first! More about Shades of Grey here. Enjoy.

A few minutes later we reached the racetrack, which was a large oval of perhaps a mile in length. Because horses were too valuable to risk on the track, the Collective had found alternatives to race at Jollity Fair. Ostriches had been briefly fashionable, as had Kudu and large dogs ridden by infants. Bicycles had been popular until the 'no gearing' leapback directive had made the races considerably less than exciting. To circumvent this some bright spark had resurrected the notion of the pre-epiphanic 'Penny Farthing', no doubt named after its inventor. The direct pedal drive on the outsize front wheel gave them a healthy top speed but also made them dangerously top heavy. With death from Mildew the most prevalent form of outtage by a long way, someone dying on the racetrack was of considerable novelty, and much applauded.

One sport, however, had dominated the Jollity Fair Race-day for more years than anyone could remember, and despite prefectural disapproval and a series of leapbacks that required a great deal of ingenuity to circumvent, the sport had yet to be banned entirely. It was Inertia or Stored Energy Racing, and East Carmine's entry was waiting for us in a purpose-made garage that backed onto the boundary. Conveniently close to the boundary, I was soon to realise. Carlos Fandango was there, tinkering with the machine, helped by an assistant dressed in a boiler-suit. The machine was called The Redstone Flyer and was unusual in that it had not four wheels but two in the manner of a bicycle, but obviously much sturdier and a good deal longer - about eight feet. Because it was gyro-driven and they were all powered up, it was standing upright on its two wheels, much like a train. The vehicle had been elegantly streamlined by tightly faired bodywork that put me in mind of a salmon. In fact, the only part of the wheels you could see were poking out less than two inches from the bottom of the curved coachwork. The gyrobike had the right hand cowling off, revealing interior workings that were a tangle of levers and sprockets, chains, belts and actuators. Although it wasn't possible to hear the flywheels going round, you could feel the hum in the ground. As I stared at the machine, it gave out a shudder that started small, escalated, then rattled the bike quite violently before calming down again. "The gyros are going in and out of phase," explained Carlos when Turquoise asked him what was wrong, "and when they do, they tussle with one another. Hello, Eddie. Did you get Imogen's Information pack?" I told him I had and he nodded agreeably, then placed a tuning fork on top of the gyro-housings, presumably to gauge which one was out of kilter. I noticed that the rider had only a single dial - a speed meter - which went up to two hundred and sixty miles in an hour. I repeated this out loud as I could barely imagine such speeds, nor what that sort of velocity might do to the human body. "We never get that fast," said Fandango, listening intently to the whisper of the gyros, "on an oval track one might manage only eighty - less if you're after endurance. We've got a good chance to win the Red Sector Jollity Fair with this." He rested his hand on the humming beast. "A triumph of inspired loopholery. No wonder Head Office can't stand it." It didn't really matter what the stored energy was so long as it wasn't electrochemical in nature. High-pressure steam or compressed air worked well, if not a little scary during the all-too-common cylinder ruptures, which could blow a rider to bits. More popular and at least tolerably safer was the inertia racer which derived its motive power from up to eight pairs of flywheels all spun up to eight thousand revolutions per minute and running in a partial vacuum. If all of this sounds obscenely technical, the reason it hadn't been leapbacked was simple - the technology that kept our trains upright on a single rail was exactly the same. And as long as the inverted monorail remained in compliance, gyro-driven vehicles were here to stay. "So listen," said Turquoise, squatting down to have a closer look at the machinery but from his look of utter confoundment, might as well have been staring at the entrails of a goat, "just confirm for me that this whole thing is compliant, will you?" "Absolutely," said Fandango, "all the Everspins do is charge up the gyros - they are disconnected when it's racing. The furthest it's ever gone on a single charge is four miles." I had been staring at the machinery for a while, and although what Fandango said was correct, I couldn't help thinking that the largest Everspin was actually attached to the back wheel by a tensioned leather belt. I put out my finger to point out the flagrant non-compliance. "That's curious-" I stopped because the assistant in the oil-streaked boiler suit had softly closed her hand around my finger. I looked around and found myself staring into Jane's eyes. It was closer than I had ever been before, and her eyes were as delightful as her nose. She was shaking her head softly, and all of a sudden, I knew how she had got to Vermillion and back in a single morning. Everspins, like Lightglobes, worked pretty much everywhere. The gyrobike might appear to be only an inertia racer, but it was actually covert Leapback - Jane could go wherever she wanted, whenever she wanted. "What's curious?" asked Turquoise, who was already filling out a release form. "Nothing at all," I replied, "quite the opposite, in fact - most uncurious. Mundane, I should say, and completely normal." Jane let go of my finger. Turquoise signed the form and handed it across to Fandango, who was already reaffixing the body panels. Jane then climbed into the bike, manoeuvred it onto the start line and then, at Fandango's signal, sped off at a terrific pace and leaving us coughing in a cloud of dust and small stones. Within a few moments she had banked sharply to negotiate the curve of the race-track and howled down the back straight. I was no expert, but it looked pretty quick to me. "Wow!" said Turquoise. "She'd win hands down at Jollity Fair," remarked Fandango sadly, "are the Council sure they can't postpone her Reboot?" Turquoise shook his head. "She's already eight hundred merits below zero, Carlos. Rules, old boy, Rules. Who's your number two driver?" "Courtland." "Then problem solved. It will keep Sally off our backs, too." Question Club Reminds me a little of the Light Cycle in Tron (The original, obviously) mixed with that little known Hopkins movie, The World's Fastest Indian ( and the race itself would probably be not unlike the Pod Race in Star Wars. You can see where I pull my influences from. Keen eyed readers will also note this was also a potential explanation of how Jane travelled so far so fast - until I had the notion of Perpetulite able to move things along on its own. If you're wondering why there is a random 'Question Club' at the end, I often write notes for myself as I'm writing, that get pushed along in what I call the 'Textual Moraine' at the coal face of the writing process. I then delete all the extraneous words and strip out the ideas. 'Question Club' was one of these. Did I use it? Can't remember. Posted 25th March 2020. |