The Day We Blew Up The Gold Mine |

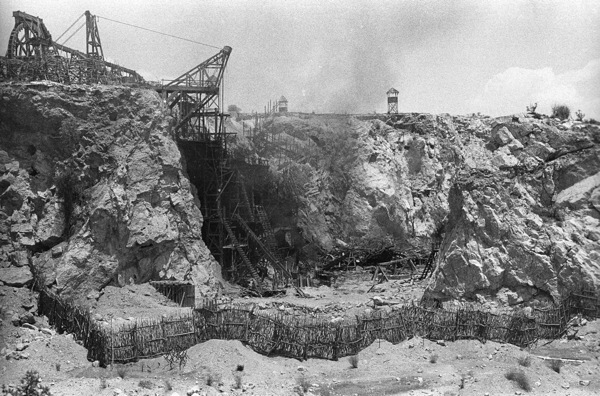

How the Gold Mine set looked mid-morning. The right side has gone, the left side intact. As it turned out, it was kind of a silver lining. In May of 1997 I wasn't a writer - I was a Film Technician. An Assistant Camera to be precise, or what was more commonly known as a 'Focus Puller' or more simply, 'Focus'. It was my responsibility to maintain the camera, make sure that we had the correct gear for the day's requirements, load the film, change the lenses, add filters, set the aperture, change or 'pull' the focus during shot if required, and most importantly, switch the camera on and off. The Mask of Zorro was a $60M movie with Antonio Banderas, Catherine Zeta Jones and Antony Hopkins. We shot it all in Mexico with a mostly American/US crew. The Director of Photography was the immensely talented Phil Meheux Bsc whom I had worked with on a few shoots before - most notably Goldeneye, and least notably, Highlander II. Because Phil was a Brit, the camera department were also Brits, so that's how I came to be there. It was a hard shoot. Long hours, a fast pace of shooting with the occasional bout of Montezuma's Revenge, but not without a great deal of fun. Given the egos involved, moviemaking is often like live cabaret. Monday 26th May 1997 was the 'Day of Days' on the shoot - the blowing up of the Goldmine, a million dollar set built in a quarry to the North of Mexico City. The set had already withstood one attempt to blow it up. We initially thought the charges hadn't gone off, but they had. The set had been built in a lattice 'basket like' manner so its resistance to lasting damage was good - if you punch a hole in a basket, you just end up with a basket with a hole in it. The same principle applied to the Gold Mine set on that first attempt. We rejigged the schedule to shoot some other stuff, and left construction to make the set safe and SPFX to try again. This is what happened on that second Day of Days. As you can see, preparations were very precise, but even so things did not run totally according to plan. So sit back, push back the furniture and have a read of the adventure that I call: The Day we Blew up

the Gold Mine. Again. Call was 9:30AM with the coach from the Posada with Sam (my assistant) on it half an hour late. All the camera hides had been strengthened since the last time. They now all have 1" timber planks to keep out the debris. In other respects the camera positions were pretty much the same, except that we added another wide camera near the reinforced firing point which had been moved 200yds further from the blast. The demolition expert this time is a huge guy named Marty who has hands like shovels and a handshake like a mantrap. Marty explained that since last Wednesday's blast was 400lbs of HE (High Explosive) and barely blew out our ear wax, today's blast would be from 2400 lbs of explosives, of the type usually used to blast road cuttings through rock. Okay then. At 10:30 Marty cleared an area in the old trailer park of 100yds radius and detonated one of these charges to demonstrate just exactly what it would do. There was a brief countdown and then a sharp detonation of raw energy as this object no bigger than a Tesco's liver sausage evaporated into a violent shockwave that thumped us in the chest, set trucks rocking and lifted the dust a foot off the road for 50ft around. "That was just one," explained Marty. "We have another 38 stuck in the set, with primer cord, maroons and all sorts of other ordinance. It's going to be loud and it's going to be destructive. I did this so you would understand." |

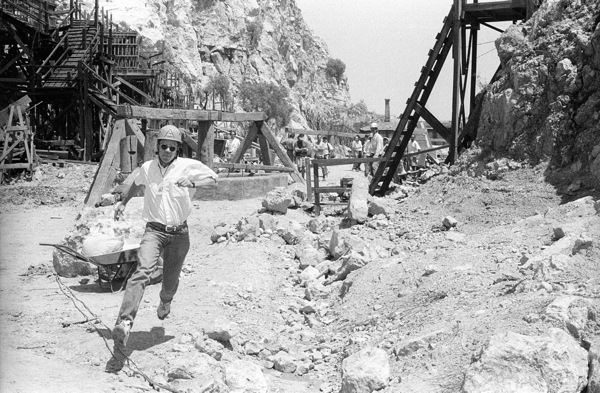

Pat runs the distance between cameras he has to start to figure out timings and route. Great bloke, BTW, and a cracking technician. We understood alright. Whilst Tom (The camera grip; he looks after tripods and tracking dollies and stuff) finished the camera hides, Pat (The 2nd Unit Focus Puller) and I figured the safest way to turn on all the cameras. Like last time, I would turn on three, Pat would turn on two, and Sam and Mariana (2nd unit assistant) would turn over the last two on the overlook. Since the radius of danger had grown considerably, we agreed that whereas Pat would run to a bunker made of 50lb sandbags at his end, I would run to Riccardo's red GMC Suburban, which would be waiting with the engine running, all the windows wound down and the rear door open for me to leap in so he could floor it. The cue for firing the charges would be a visual cue from the Suburban driving away. Marty in the firing point had a stopwatch and would start it as soon as he saw Pat start his first camera. This was key. Back in those days we shot on film, and with limited sizes of magazine. The camera was running at 96 frames per second and had only a minute of film (24FPS is usual; 96FPS would slow down the action four times), so when the stopwatch reached 45 seconds and nothing had happened, Marty would abort and we'd go and reload. If anything went wrong we were to put our hands on our heads except me who was out of sight of the firing point, but since my red Suburban was their cue to fire, nothing could happen to me if I was late or delayed, or fell over. We spent the last few minutes rechecking camera speeds, remote starts, focus, apertures, etc, until SPFX (Special Effects), art department and everyone else was ready, the Assistant Directors had locked up the area, and the top of the mine had been checked for any public who had strayed into the danger area. When all of us were ready we had a safety meeting so everybody knew just what exactly was going to happen, and when this was done and all last minute upsets and questions dealt with, the set was cleared to about 700 yds away, the trailer park having been moved down to the base camp on the road a mile distant and only Firemen and Medics in the support trench about 500yds away. The sun was shining brightly, there was barely a cloud in the sky, and almost complete silence as Pat, Dooper (Special Effects Technician; he was there to set a few fires and smoke effects) and myself waited in the vast and very empty set for the "Turn cameras!" command from George (1st assistant director). There is always ten minutes or so for the SPFX boys to rig their final wiring and prepare for the blast, so after all the excitement, there is suddenly a very real calm before the storm. The only sounds to be heard was the twittering of a small bird from his usual perch on the rock above us and the idling engine of Riccardo's Suburban as he waited for me with the rear door open. I looked over at Pat who was busying himself piling more rocks on top of one of his camera positions, and then at Dooper who was testing the blow lamp that he would use to set the fire alight. Curiously peaceful. I looked up at the set and could see how the lattice of woodwork was draped with wires, the charges taped to the wooden supports and all looking very innocent. |

The toppermost of the cameras I had to switch on, covered in a heavy frame of 4X2 and sandbags. Probably one of the Arriflexes. You can see my Surburban getaway car waiting in the background. It was closer than this on the day. "Flame up!" came the command down the bullhorn. Dooper fired up all the rags soaked in gasoline, working his way up the set from the furthest point to the Suburban which would also be his escape route. After what seemed to be an age, George bellowed: "Roll cameras!" and Pat and I quickly turned on our cameras and headed for our escape routes. I leapt into the back of the suburban and Riccardo floored it immediately, almost throwing me into the back. I pressed one foot against the roof as we drove down a shallow slope and as we reached the main road out of the set, the whole ground seemed to shake as a noisy "Prrrrrap!" lasting less than a second caused the dust on the road to jump about 6 inches in the air. I knew without looking that something had gone wrong; the "Prrrrrap!" noise I had heard were the charges being let off in quick succession. Surely that brief report wasn't all 38 of them? As it turned out, it wasn't. We drove up to the firing point to see a collection of long faces; only a third of the charges had gone off. The right hand side of the set had failed to explode. Marty drove down there as another charge went off, and the fireman were pulled in to put the fire out before we didn't have a set to blow up. Everyone is an instant expert in times like this and a million theories were put forward, the most popular being the one closest to the truth; since all the charges are fired by electricity, one of the first charges must have thrown some debris into the firing cables, severing them completely and stopping half the set from detonating. After 20 minutes we were allowed in to check the cameras and discover more bad news. Of the five cameras actually in the danger zone, only one was without a problem. Two of the cameras had cut the moment the charge went off, leaving most of the film unexposed in the magazine. On two of the others the concussion had shattered the filters, making the shot unusable. The only camera that had functioned properly apart from the two on the overviews was the camera that was covering the area that didn't go off. So lunch. Pat and I talked about the problem and concluded that the push-to-start, push-to-stop remote switches had been "Push-to-stopped" by the concussion, which also damaged the two filters. Since we reckoned that it was the shockwave moving the filters in the matte box, we would tape the filters in a single pack and then tape that to the front of the lens and discard the matte box altogether. If the filters moved, the camera moved with them. |

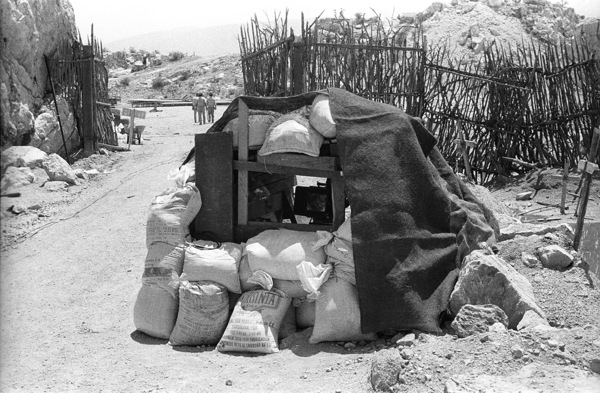

Pat's second camera he had to switch on - his escape route was out of those gates behind. Sandbagged heavily, but impossible to make completely safe. This looks like one of the wide cameras - and taken before the first blast. There were lots of theories as to what we would do next. leave for Guaymas, wrap, come back, build a model, whatever, but by the end of lunch and in consultation with Marty and the director we decided to re-rig the charges and fire it again. I explained to production my theories for what went wrong, telling them - to scotch the inference of incompetence - that between Pat and myself we have 30 years of experience and 63 features, and neither of us had come across a blast strong enough to depress a remote switch. So we all re-rigged the shot, two cameras were moved completely, one had a tighter lens and the two overview cameras stayed the same. By 3:30 PM we were ready to blow it again. I had a longer run this time since we could not use the remotes, each camera had to be visited in turn and switched on manually, rather than cluster the remotes near one camera. I had to start one camera, run down the slope to another, switch that on and then run to the next, which would be Pat's cue to start his 1 minute 96 framer. So we waited for the command in the same silence that had pervaded the area the last time. Only now the sun had gone in, the bird had wisely vanished, the clouds covered the sky and it seemed to get darker every minute with an impending storm. Light rain started to fall and an ominous peel of thunder rumbled above our heads. The light dropped some more and we had to change the apertures on the cameras. This done we stood by again, the lightning getting closer. Suddenly, Peter yelled at us: "Get over by the Suburban!" We obeyed -you don't argue with SPFX technicians when there is 1500lbs of HE 100ft away - and the explosion was abandoned for the time being as the rain started to fall more heavily. We were evacuated away as the sort of static charges that preclude electrical storms can set off detonators, and Peter had felt a tingling of static from his high vantage point near the set. The sky darkened even more and the heavens opened. We all took refuge in the suburban as the rainstorm got worse, and we waited and watched as the electrical storm moved closer, passed and moved on, the downpour opening up gullies of water in the surrounding hills. We couldn't get in to cover the cameras in case the charges were set off, so we had to sit and wait it out, hoping that the hides would offer the cameras some sort of protection from the elements. We sat there for an hour. Eventually, the rain lessened, the lightning moved on and we were almost out of stories. SPFX allowed us in and we set about cleaning filters that had got covered with dirt and mud and resetting everything for another blast as Phil the DOP had predicted enough light to blow the mine in under half an hour. So we set up once more, rechecked everything, set apertures, had another safety meeting, and ba-da-boom, ba-da-bing, Pat and Dooper and I were waiting for the word again. |

The right hand side of the gold mine and the destruction that should have befallen the entire set. We were allowed in only when deemed safe by the SPFX crew, but even so, the firefighters went first to stop the set burning down, which was key in getting another (third) bite at the cherry. "Turn cameras!" Finally. I switched on my top camera, made my way gingerly down the slope now slippery and wet, picked my way to the second camera, then the third and finally out into the suburban. We had made it out to the road and stopped by the time the charges went off. Wood was thrown at least a hundred feet in the air as the rest of the mine blew up. Screams and yells from the assembled crew punctuated the air as the American SPFX team gave each other high fives and yelled and whistled. The British crew were heard to say 'jolly good'. The set was matchwood and the quarry looking like it had been scraped clean of any evidence we were there, apart from a few pieces of wood still clinging stubbornly to the face. Bits of wood had been thrown over two hundred yards away and covering the set was a thin layer of what could only be described as "wood dust." It was quite a bang and probably the quickest way to strike a set. "About bloody time," said Campbell. We went in to check cameras and found that -thankfully- the least interesting shot was the only camera with a problem: the camera had run for twenty feet and then the film had snapped, missing the action altogether. There was enough in the other cameras, though, but we will have to see rushes to be absolutely sure. And that was a wrap. Nothing else could be done that day, so we called for the two camera trucks and started the laborious task of cleaning all the cameras. A hard day. We were all tired and knackered from running this way and that - but it had been exciting and full of high adventure. Looking back on it now, it would probably be regarded as not a very safe way of doing things, but that would be a wrongful assumption. Marty and his team left nothing to chance. There were safety meetings, a slow pace to the set-up, failsafe safety strategies and, most importantly, a highly professional and safety-conscious mindset in us all. Interesting day, to say the least. Jasper Fforde, Recalled July 2020. |